It is for great reason that Canada has a global reputation as an international peace-keeping nation.

With approximately 13,023,141 active-duty members (both males and females) and 658,300 veterans ranging between 18 to 93 years of age, the Canadian Forces (CF) are an important part of the nation’s image at home and abroad.

These highly trained Canadians are repeatedly called upon by the United Nations (UN) and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to participate in humanitarian, security, peace-keeping, as well as counterinsurgency and guerilla missions.

War and peace-keeping expeditions include distinctive work arrangements and entail life-altering events (such as combat experiences) that often impact one’s well-being far beyond the physiological realm.

More often than not, these types of combat experiences in which members of the CF are called to partake in and engage impose a great threat and result in a myriad of physiological and psychological strain, both immediate and long-term – often making it hard to function and integrate within their society (family, friends, civilians) after and during their service.

Events that have been found to lead to these detrimental effects on the mental health of military personnel include those such as a death of fellow service members, the killing of others, roadside or mine bombs and bombing, failures in leadership (be they legitimate or presumed), friendly fire, and other acts that are deemed as challenging and transgressive to someone’s core values, beliefs and/or morals.

The typical tasks and responsibilities of CF members include missions to conflict-ridden places, such as Bosnia-Herzegovina, Rwanda, Iraq, and Afghanistan (amongst others), and in a culture that is dominated by the need for its members to be strong and fearless, it is not surprising why veterans are unable to reconcile their altered reality.

Statistics Canada reports that 1 in 6 full-time Regular Force members of the Canadian Armed Forces experience symptoms falling within at least one of the following disorders:

- Major Depressive Episode,

- Panic Disorder,

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder,

- Generalized anxiety disorder,

- Alcohol abuse or dependence.

Of all the prementioned disorders, depression was the most common, with approximately 8.0% of Regular Force members reporting symptoms within the past 12 months.

Additionally, the 12-month rates for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and panic disorder were twice as high among Regular Force members who had been deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan compared to those who had not (this suggests that the quality of certain Combat Experiences (CE) has a greater impact on one’s mental health than others).

CF members have also been identified as having higher rates of depression than the general Canadian population.

Now, although resources have been implemented in trying to help mitigate the mental health strain from exacerbating (e.g., leading to suicide or family violence), there seems to be a treatment gap as emphasis and attention is given to disorders such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), which do not necessarily account for the challenging and transgression of one’s core values, beliefs, and morals.

Service gaps can have deleterious and detrimental effects on service members and may perpetuate problems if left untreated properly.

This brings into light many inquiries, such as, what are morals, what violates, challenges, and/or transgresses one’s core values and/or beliefs, how and/or why do such events affect someone’s mental health, and what are the symptomology or manifestations of such experiences?

Moral Injury in the Military

The word injury derives from the Latin word injuria, meaning a wronging or a “violation of another’s legal right” (Goldberg, 2011).

In this context, it is used to label the violation or wronging – injury to – a moral value or a strong belief. Events within the military experience that lead to this type of injury include:

- The direct responsibility for death to enemy combatants,

- Wrongly taking the life of a civilian,

- Seeing women and/or children who they are unable to help abused or wounded,

- Unexpectedly seeing remains and dead bodies of those they know (other service members) and/or don’t know.

These disturbing and profound experiences have been described as Potentially Morally Injurious Events (PMIEs), as they have the potential to deeply wound values and moral beliefs of preserving and protecting the sacredness of life and/or conducting oneself in a prosocial manner.

A review of the research on PMIEs suggests that they can be directly experienced, witnessed, or even learned about.

As it is understood, PMIEs may lead to a myriad of psychological, emotional, and spiritual disruptions and can be experienced in different ways, most of which are not accounted for nor captured by Post Traumatic Stress disorder – one of the most commonly associated disorders to war-related trauma.

Up until recently, clinicians and researchers have focused most of their attention on the implications of life-threatening trauma as opposed to the impact of events with moral and ethical implications.

Its increased recognition within the military setting was first described by psychiatrist and researcher Jonathan Shay, who suggested that Moral Injury occurs when three features are present, those being: “(1) there has been a betrayal of what is morally correct; (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority; and (3) in a high-stakes situation”.

In Dr. Shay’s description of Moral Injury, the transgressor is not the individual but another entity, specifically a power-holder (i.e., military leader).

Although this definition captures aspects of Moral Injury that have otherwise not been considered by other war/common military diagnoses (Depression and PTSD), there still lies ambiguity within its definition. What is “morally correct” and what are “high-stakes situations” may differ from individual to individual, making such an experience one that is very subjective and perplexing.

Since Shay’s introduction to this syndrome in Achilles in the Iliad, more work has been done pertaining to morality, Moral Injury, military culture, and wars, thus, bringing into light a more universally accepted definition for Moral Injury which proposes that it is a “perpetration, failure to prevent, witnessing of, or learning about an act that transgresses deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”

It is without question that there are overlapping components of PTSD and Moral Injury, but there are also distinct differences (refer to Figure 1 below). PTSD has a triggering event of actual or threatened death and/or serious injury.

For example, PTSD is characterized by fear, a “startle” reflex, memory loss (blocking), and flashbacks. In contrast, as previously mentioned, Moral Injury entails an act that one believes to have violated a deeply held moral value.

An individual’s role at the time of the event is also a factor, that being, whether the individual had an active role as a perpetrator or a victim.

Symptoms typical of both PTSD and Moral Injury include, but are not limited to, anger, depression, anxiety, insomnia, nightmares, and self-medication with alcohol or drugs. The distinction is apparent with PTSD being a fear-based, singular event and Moral Injury being more comparable to taking part in a morally ambiguous set of combat events.

Literature suggests that although Moral Injury shares similar features to PTSD (as seen in the figure above), it is still proposed to be a distinct syndrome.

In that, symptoms that are central to Moral Injury (guilt) differ from those of PTSD (fear). Additionally, while PTSD models focus on exposure to a “threat,” Moral Injury captures those events that invoke moral conflict, which may or may not involve threat.

It is important to note that Moral Injury is not classified in the Diagnostics and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) at this time and that earlier versions of the DSM classified PTSD as an anxiety disorder.

This is essential to know because although PTSD is no longer classified as an anxiety disorder, the most commonly used treatments for PTSD are still generally those that are fear-based and built on realms of anxiety.

Moral Emotions

It has been suggested that moral emotions, such as guilt and shame, differ from nonmoral emotions, such as fear and anger (PTSD-associated emotions). This notion is based on the understanding that moral emotions, unlike other emotions, have a primary concern with the preservation of social relationships and conducting oneself in a prosocial manner.

Five categories of Moral Injury emotions have been described in the literature and include:

- Other-condemning emotions,

- Self-condemning emotions,

- Other-suffering emotions,

- Other praising emotions,

- Self-praising emotions.

Emotions such as anger, contempt, and disgust are those in which the individual considers another to have an inferior sense of morality or lack thereof, and this falls under what has been classified as other-condemning emotions.

Guilt and shame, two of the hallmark traits and key emotions of Moral Injury, fall under self-condemning emotions, and these are key differentiating emotions of one who experiences Moral Injury from PTSD (internal experience of the involved individual).

Of the formerly mentioned emotion categories and moral emotions, two will be further explained in this post, those being anger and guilt.

Anger

The emotion of anger is understood as a primitive and biologically necessary primary emotion innate to all human beings. Emotional experiences of anger are subjective and may vary from irritation (a mild form of anger) to rage manifested through aggression and or violence (severe).

Studies on anger have characterized it as an emotion that is based on cognitive biases reflecting an oversensitivity to violation, exaggerated prediction of a stimulus, and subjective interpretation.

Anger also can function as a secondary emotion. This is through its association with fear (as in the case of PTSD), whereby the experiencing of fear leads to intolerable strong feelings of vulnerability, uncertainty, and/or uncontrollability and, in turn, becomes a discriminative stimulus for the secondary emotion of anger – as the experiencer aims to re-establish control.

Although it may seem like a maladaptive response and has gained a bad reputation, as it often leads to more negative consequences, anger is intended to serve as an adaptive function.

As an emotion, its basic purpose is to prepare and protect human beings from responding to real threats in their environment. Such an emotion is understandable at times of war.

However, when generalized to contexts beyond those in which it is likely to be useful and adaptive, this otherwise normal emotion can lead to chronically heightened arousal and is associated with dysfunctional and problematic behavior – which is what is seen in veterans and service members outside the military setting.

Studies on veterans and service members who reported problems with anger described experiencing anger in all aspects of their lives. Examples included becoming angry with family members, friends, work acquaintances/colleagues, classmates (for those who returned to school), and community members.

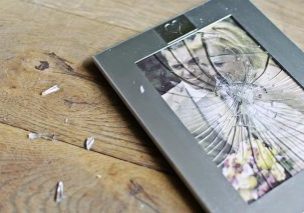

Anger was also a culprit of broken marriages (divorce), loss of jobs, and broken friendships and family ties. Thus, one can see the vitality in understanding anger as an emotion outside of war and combat experiences as service members try to reintegrate into society.

Guilt

Guilt as an emotion is the feeling one experiences when they feel they have committed a wrong by breaching and/or compromising a rule or law they believe or consider to be important and valid.

This may be a social norm or a societal value, a legal law, a cultural, religious/spiritual, and/or even internal values they uphold in high regard.

Guilty feelings are understood to arise from the cognitive dissonance that stems from the gap between one’s self-image as a law-abiding, prosocial individual and the actions which may contradict such views.

How guilty one feels depends on how seriously they consider the offense to be. Considering that guilt is a key feature of Moral Injury, whereby there is a “transgression of deeply held moral beliefs and expectations,” one can see the importance of this emotion and a greater understanding of how combat experiences influence and lead to the manifestation of such a strong and potentially self-destructive emotion – which may lead to feelings of unworthiness and the need to alienate oneself, to suicidal ideation.

Moral Injurious Experiences

Moral Injury Experiences are highly arousable situations that are not only ambiguous but often occur spontaneously within the military context eliciting immediate primitive emotions, such as fear and anger, as well as guilt and shame as one experiences a potentially morally injurious event.

The effects of these experiences of combat undoubtedly have a damaging impact on service members as they are exposed to rather unusual morally, emotionally, psychologically, and physically challenging situations.

Previous studies on Moral Injurious Experiences (during and post-combat) have found a correlation between these experiences and self-depreciation, loss of trust or a sense of betrayal, social problems, spiritual issues, and other psychological problems.

Attending to Moral Injury

When a moral conflict is experienced in ordinary situations (i.e., a physical fight), people are often able to resolve the conflicts with their personal values, which avoids their perceiving transgressions (e.g., stopping the fight, calling the police, discussing with a family member or professional).

However, the moral injuries that are often being faced by military personnel and veterans are those that are beyond such situations. Moral Injury leads to a myriad of psychological problems above the injurious moral emotions of guilt and anger.

If the dissonance is resolved, combatants are able to continue their mission, service, and personal life without (or with little) impairment. However, if the dissonance goes unresolved, guilt, shame, alienation, demoralization, self-handicapping, and interpersonal problems may result, among other negative consequences.

For these reasons, if you or someone you know and care for is experiencing Moral Injury, it is important to direct them to services that may help alleviate the strain they are experiencing because of their Moral Injury.

References:

(Lee, Aldwin, Choun, & Spiro, 2017)

(Drescher et al., 2011)

(Hastings, Northman & Tangney, 2002).

(Furukawa, Nakashima, Tsukawaki, & Morinaga, 2019)

(Porter et al., 2018).

Thériault et al., 2019)

(Frankfurt & Frazier, 2016)

(Koenen, 2018).

(Shay, 2014)

(Litz et al., 2009).

(Wood, D., 2014).

(Maguen, & Burkman, 2013)

(Drescher et al., 2011).

(Haidt, 2003).

(Deffenbacher, Demm, & Brandon, 1986).

(Quick et al., 2018).

(Kemper, 1987).

(Porter et al., 2018).

(Furukawa, Nakashima, Tsukawaki, & Morinaga, 2019)

(Malti, 2016).

(Hastings, Northman & Tangney, 2002).

(Drescher et al., 2011)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Khaoula Louati

Ms. Louati is both a Ph.D. (C) in Psychology and licensed RN and a regular contributor to the blog.

MORE POSTS BY THE AUTHOR